The Vatican’s recent embrace of cartoonish symbols, notably the blue-haired mascot named ‘Luce,’ signals a concerning transformation within the Catholic Church, moving away from its rich artistic heritage towards a more commercialized and trivialized approach. This shift may seem superficial to some, but it reflects deeper historical and cultural currents that warrant closer scrutiny. The historical context suggests that this development is not merely a departure from traditional aesthetics but part of a broader trend that devalues the profound and the sacred in favor of the mundane and kitschy. The symbols now being adopted could undermine the Church’s historical reliance on majestic art as a means of connecting with the divine and communicating complex theological concepts.

The enduring query of whether life imitates art or vice versa poses important implications for understanding the role of art and artists in society. It raises the question of whether artists serve as agents of social change, influencing culture, or simply reflect the existing cultural landscape. Acknowledging that both perspectives hold some truth allows for a more nuanced exploration of artistic expression. However, what frequently goes unaddressed is the philosophical foundation that underpins the artists’ work. This philosophy not only influences the creation of art but also dictates how society perceives and interprets artistic endeavors. As such, the underlying ideologies can shape cultural values and norms over time, which is particularly relevant in examining the Church’s current artistic direction.

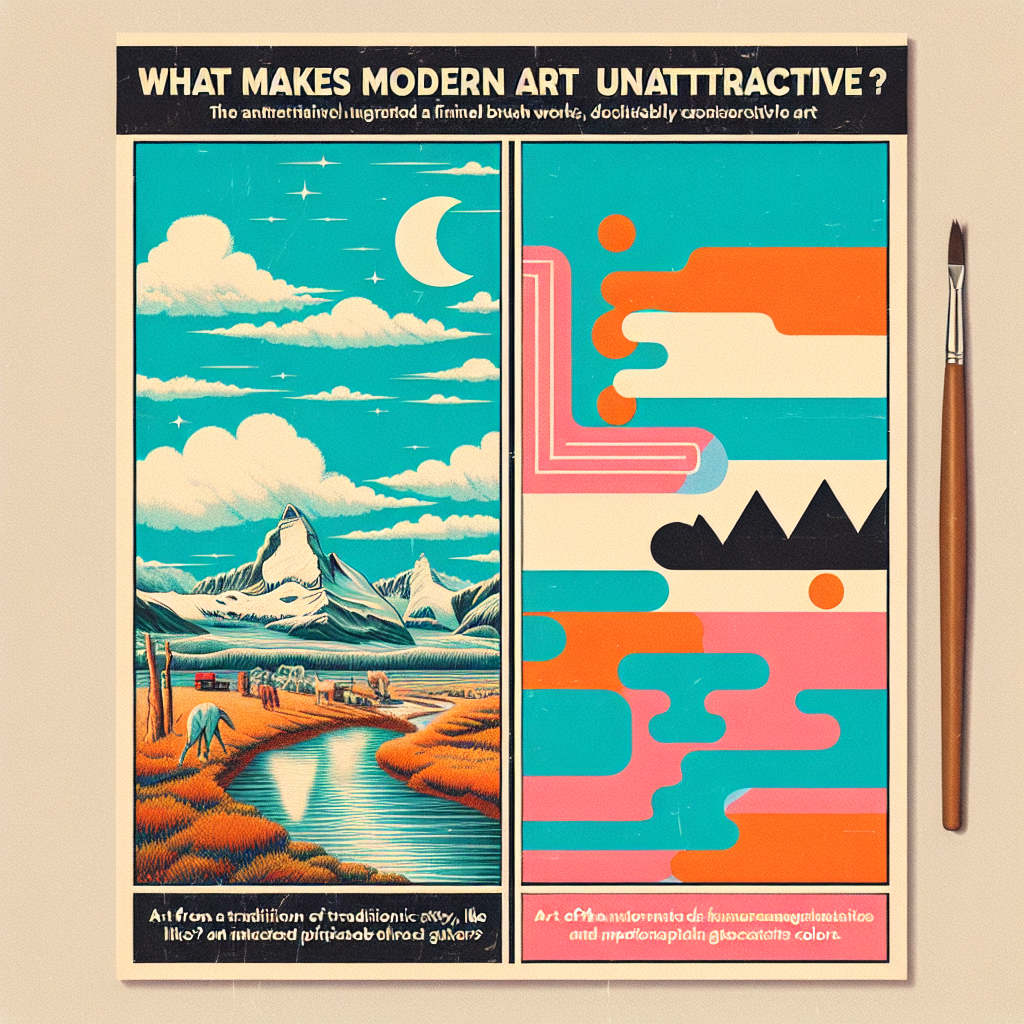

Modern art traces its roots to the sociopolitical upheaval of the French Revolution and the Enlightenment, but it fully emerged in the late 19th century. Influential artists like Goya paved the way for movements such as Romanticism and Impressionism, which gradually evolved into Post-Impressionism and the avant-garde styles epitomized by Les Nabis and others. While much of the discourse surrounding art history emphasizes an evolution in techniques and styles, the philosophical underpinnings of these artistic movements often remain overlooked. A prominent figure in modern art, Eugene Delacroix, suggested a troubling philosophy when he remarked that the pursuit of perfection is an exercise in futility. This perspective excuses a lack of precision and truth, fostering a cultural acceptance of art that prioritizes impression, emotional resonance, and subjectivity over beauty and truth.

Contributing further to this philosophical shift, artists like James Whistler proclaimed that art arises spontaneously, independent of intellect or craft, which further reduces the significance of intentionality and truthfulness in artistic creation. This notion displaces the objective pursuit of truth that arguably should characterize art, favoring instead a subjective interpretation of reality that emphasizes the artist’s personal experience and emotional states. Consequently, the dialogue surrounding the very essence of art becomes obscured as it veers away from objective criteria, allowing for a more widely varied and often debated interpretation of what qualifies as art.

The transformation championed by artists like Paul Cezanne marks a critical turning point, as he declared that genuine art originates from emotion rather than from an endeavor to capture beauty or truth. This reorientation from the traditional ideals of aesthetics towards the subjective emotive experience signifies a pivotal moment in artistic philosophy. Rather than serving as a reflection of the universal and the divine, art becomes a canvas for personal expression of individual experiences and feelings, which significantly alters its interaction with cultural and religious narratives. The implications of this shift are profound, as it invites a diminished appreciation for the established artistic tenets that have historically sought to portray the sacred.

This movement in art coincides with the rise of Modernism, which has been identified as a heretical strain of thought in Catholic teaching. Popes like Pius IX and St. Pius X recognized the challenges posed by modern ideologies that favor subjective experience over objective truth. The interconnectedness of Modernism and the evolution of modern art reveals a concerted effort to redefine the purposes and definitions of art, suggesting that both movements any share a common foundation—an emphasis on personal experience and emotion. In this light, the Church’s current artistic choices may reflect a broader capitulation to these trends, signaling an alarming departure from its historical commitment to a transcendent understanding of beauty, truth, and faith.