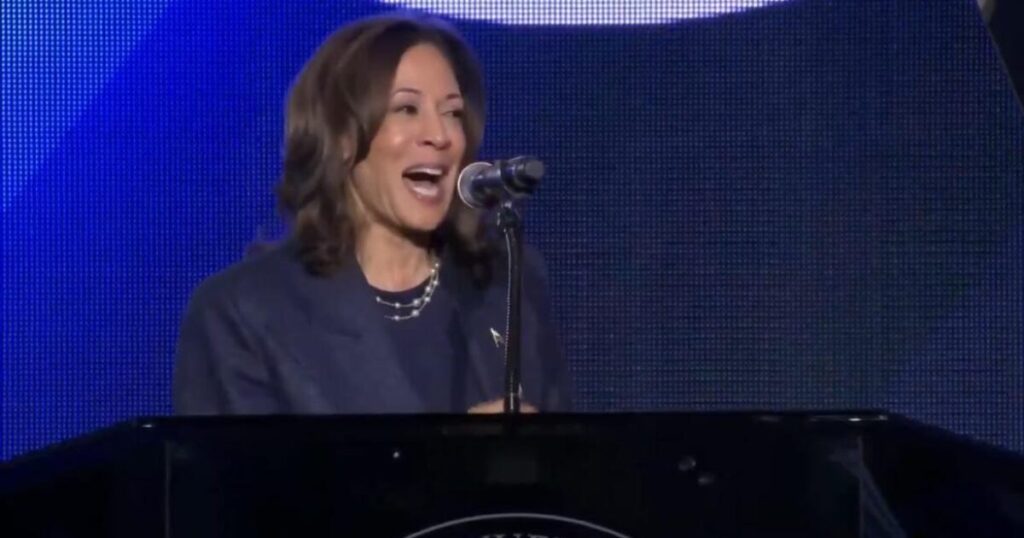

On the eve of a significant election, Vice President Kamala Harris delivered an impactful speech at the Greater Emmanuel Institutional Church of God in Christ in Detroit, a venue steeped in community and faith. Harris emphasized the importance of faith as a driving force behind collective action, stating, “Growing up in a church, I learned that faith is a verb, and we show it in our actions, in our deeds, in our service and in hard times.” Her remarks encapsulated her belief that faith extends beyond personal conviction, urging parishioners to engage actively in shaping the nation’s future. She highlighted the resilience of Americans disenchanted with division and strife and expressed optimism that unity could pave a new path toward justice.

In her speech, Harris highlighted the significant potential for healing and reconciliation among Americans, regardless of their political affiliations. She articulated her vision of a nation where individuals come together to overcome hatred and negativity: “I see a nation determined to turn the page on hate and division and chart a new way forward.” This message resonated with the congregation, suggesting that common ground could be found even amid stark political differences. By bridging the divide, Harris envisioned a narrative where action and compassion guide the nation’s progress toward equity and justice.

However, Harris’s speech was not without criticism. Many observers noted her use of a “fake preacher accent” during parts of her address, which sparked reactions on social media. Critics argued that her mannerisms seemed inauthentic and suggested an attempt to mimic the African American church tradition for political gain. This phenomenon of politicians adopting particular styles of speaking or engaging could be viewed as a form of performative outreach intended to appeal to specific demographics, ultimately raising questions about authenticity in political rhetoric.

The echoes of Harris’s speech can be traced back to similar sentiments expressed by former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. Clinton famously invoked the phrase “I don’t feel no ways tired” during her 2007 campaign, a line deeply rooted in the African American church tradition. Like Harris, she utilized the cadence and phrasing characteristic of the Black Baptist Church to connect with her audience, demonstrating how language and cultural references can be leveraged in political contexts. This strategic use of church rhetoric illustrates how politicians seek to embed themselves within the cultural fabric of their constituents, though it can also lead to accusations of insincerity.

While both Harris and Clinton drew from religious traditions to convey their messages, the reception of such performances can be deeply polarized. Some constituents appreciate these appeals as genuine expressions of solidarity with their experiences, while others criticize them as mere tactics for electoral gain. The challenge for politicians lies in navigating this complex terrain of authenticity versus performance, particularly within communities that place high value on sincerity and connection through shared beliefs and practices.

Ultimately, Harris’s remarks at the church reflect broader themes present in contemporary American politics—issues of identity, representation, and the fine line between authenticity and performance. Whether viewed through the lens of hopeful progress or skepticism regarding political motivations, her address underlines the importance of faith and community engagement in the quest for justice. The dynamics of such speeches and their reception will likely continue shaping political narratives in the lead-up to the election, illustrating the complex interplay between language, culture, and political identity.