The United States employs the Electoral College as a distinctive mechanism for electing its president, a system rooted in the Constitution created by the nation’s framers as a compromise to avoid congressional selection. This system assigns electors based on each state’s representation in the House of Representatives plus two senators, culminating in a total of 538 electors. A candidate needs a minimum of 270 electoral votes to secure the presidency. During the 2000 and 2016 elections, both George W. Bush and Donald Trump won the presidency despite losing the popular vote, leading to debates about the fairness of the system. Critics, primarily from the Democratic Party, argue that the Electoral College disproportionately advantages Republicans and advocate for a transition to a direct popular vote election. However, such a change would necessitate a constitutional amendment, highlighting the challenges inherent in reforming a long-standing electoral framework.

The mechanics of the Electoral College involve a complex interplay between state-level popular votes and the allocation of electors. Each state’s electors are bound to vote for the candidate who wins the statewide popular vote, with the exception of Maine and Nebraska, where electoral votes can be split according to congressional district results. This creates situations where votes in smaller states carry more influence nationally compared to those in more populous states, leading to electoral outcomes that can conflict with the overall popular vote. As a direct consequence, candidates often prioritize campaigning in battleground or swing states—regions where electoral outcomes are uncertain—rather than focusing uniformly across the entire nation. This trend has notable implications for campaign strategies, as candidates must calibrate their approaches to maximize electoral victories rather than popular support.

Electors, who are selected by state political parties, typically embody individuals aligned with their party’s interests and do not include current members of Congress. Upon the completion of state elections, electors convene in their respective states to cast votes for president formally. In the context of a tie or if no candidate garners the requisite 270 electoral votes, the election process shifts to the House of Representatives, where each state delegation casts a single vote to determine the winner. Although such scenarios are rare, having only occurred twice in the nation’s history, they demonstrate a crucial feature of the Electoral College system that underscores the interplay between federal and state governance.

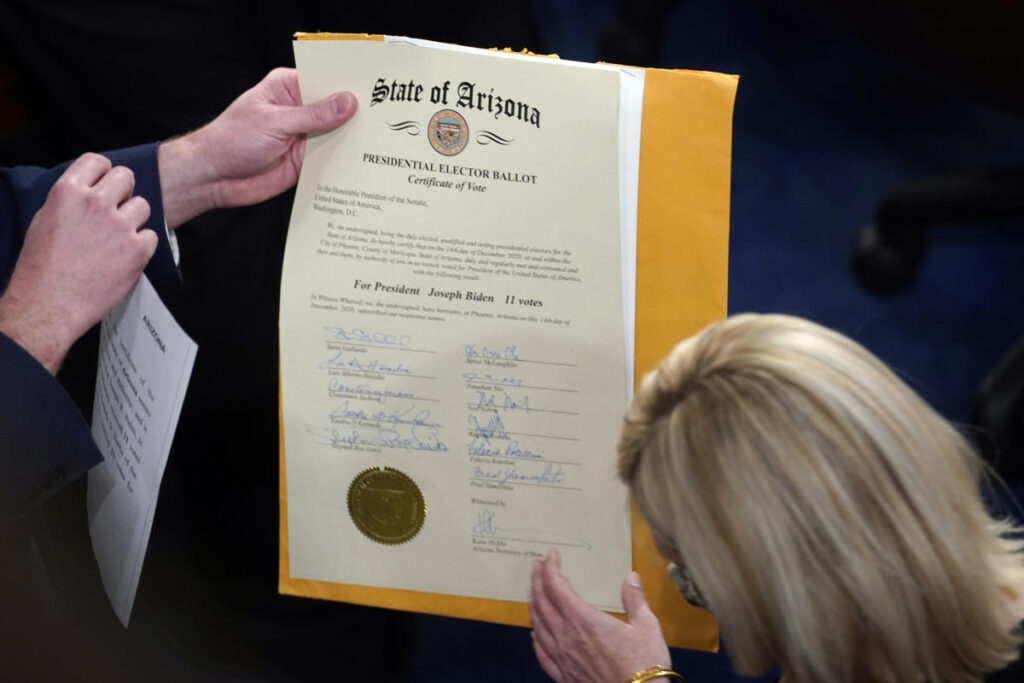

Once the electors cast their votes, they must certify their results and send documentation to Congress, which conducts a formal count on January 6 following the election. This process involves opening certificates from each state and ensures transparency and legitimacy in the electoral process. Notably, lawmakers retain the right to object to states’ electoral results during this congressional session, a point that became particularly contentious during the 2021 certification when several Republican lawmakers challenged the results from Arizona and Pennsylvania. The aftermath of the Capitol riot on January 6, instigated by efforts to overturn the results of the 2020 election, prompted Congress to amend the Electoral Count Act to clarify the vice president’s role and reinforce the challenges of objecting to certified electoral outcomes.

The evolving narrative surrounding the Electoral College reflects broader questions about democracy in the United States, specifically regarding representation and the significance of the popular vote. Critics highlight how the system can negate the voice of voters in populous states, where their votes weigh less heavily in the overall electoral calculus. Conversely, proponents argue that the Electoral College protects the interests of smaller states and preserves the federal nature of the American republic. This ongoing debate fuels discussions about potential reforms, including attempts to shift toward a direct national popular vote.

As the 2024 presidential election approaches, the implications of the Electoral College remain highly relevant. Candidates must navigate the complexities of this system, balancing strategies to secure both electoral and popular support. The continued scrutiny of the Electoral College’s fairness and effectiveness underscores the need for public discourse on how best to represent the diverse electorate of the United States while adhering to the foundational principles established by the Constitution. Understanding the mechanics and controversies surrounding the Electoral College is crucial for voters as they engage with the democratic process.

In summary, the Electoral College is a distinctive and controversial element of the American political landscape, shaping the strategies and outcomes of presidential elections. While it provides a framework for electing leaders, it simultaneously raises significant questions regarding representation and the principle of one person, one vote. As debates about election reform continue, the necessity for an informed electorate becomes increasingly apparent, ensuring that all citizens comprehend the mechanisms that govern their democratic processes. The AP’s initiative to explain these aspects of American democracy serves as an invaluable resource for voters aiming to articulate their positions and participate meaningfully in the electoral system.