The cyclical nature of rise and fall experienced by great nations finds a poignant reflection in the contemporary landscape of the First World, positing that civilizations ascend to greatness through determination and hard work only to decline into a state of complacency and apathy. This latter phenomenon seems to be uniform across many First World countries today, leading to an unsettling prediction that such apathy may inevitably usher in a new form of bondage. Historically, periods marked by citizen apathy have been precursors to significant social and economic decline, with citizens gradually becoming subjects of a state that exercises control over their lives in more insidious ways than outright tyranny. This decline signals a grim outlook where the populace risks descending into a serf-like existence under authoritarian governance, despite the superficial trappings of democracy that allow them to cast votes in elections.

In examining the mechanisms of modern governance, one could argue that while past rulers like the Sheriff of Nottingham wielded their power overtly through force, today’s state operates with a more sanitized approach. Modern citizens are less directly coerced but are instead compelled to surrender their wealth voluntarily under threat of financial retribution. When people fail to meet state financial obligations, they face grave consequences such as property seizures and incarceration, illustrating a clear continuance of coercive governance reminiscent of feudalism, albeit with a contemporary veneer. The illusion of a democratic society is maintained, where citizens purportedly have a say in their government through elections, but the reality is that financial pressures mean that only those with considerable resources can effectively influence political outcomes.

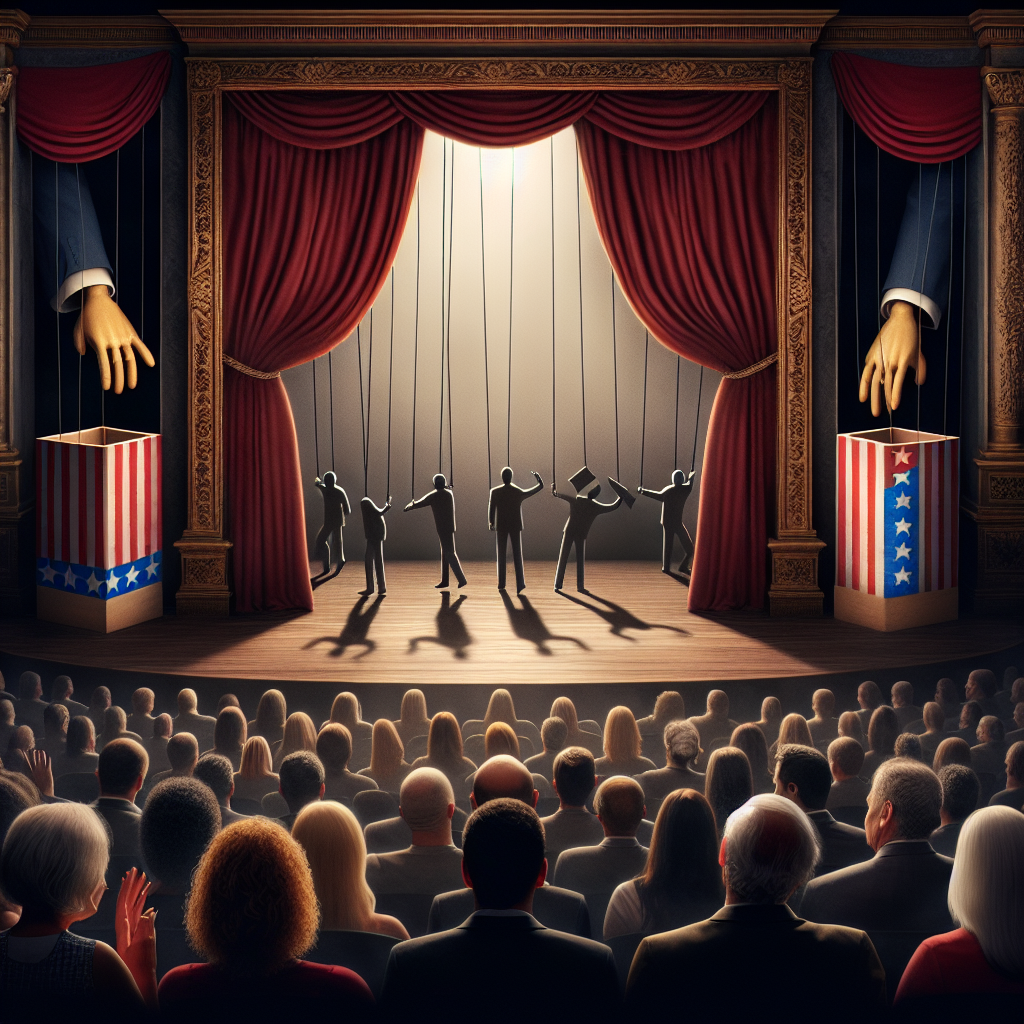

The essence of the democratic process is grounded in the belief that citizens elect representatives to safeguard their interests. However, this process is heavily compromised by the role of money in politics. Campaign financing has created a vicious cycle where candidates, reliant on donations for their electoral pursuits, end up beholden to wealthy donors and special interest groups who expect returns on their investment in the form of favorable legislation or government contracts. As a result, the “voters” become unwitting participants in their own subjugation, funding arrangements that solidify their oppression while providing little recourse to demand accountability or change from elected officials. This dynamic erodes the very freedoms that democracy professes to uphold, enabling a cycle where government perpetuates its need for revenue while citizens become disillusioned with the notion of representative governance.

Analyzing the political environment in many First World nations reveals that the supposed benefits of a two-party system often result in a reduction of freedoms across the board. Voters typically perceive alternating political control as a mechanism for balancing social and economic liberties, but this assumption is misleading. The agenda of each party often leads to a pendulum effect where neither social nor economic freedoms are significantly enhanced, resulting in a cumulative erosion of rights over time. Liberals may advocate for social freedoms while imposing restrictions on economic freedoms, while conservatives might aim to regain economic liberties at the expense of social rights. Collectively, this pattern hints at a systemic decline, misleading voters into believing they are partaking in a democratic process when, in reality, both parties converge toward a common goal of maintaining control and expanding state powers.

As discontent brews among citizens who, despite their ideological differences, find themselves facing similar grievances under varying leadership, the potential for civil unrest becomes more pronounced. The question arises whether this dissatisfaction might coalesce into a more formidable movement or expression of rebellion against the status quo. With rising awareness of the systemic failures of political systems across the First World, citizens may seek to articulate their discontent in demands for real change, rather than the mere cyclical alternation of party rule that has characterized their recent political history. Observations from current events suggest that frustrations with political ineffectiveness could lead to confrontations, questioning whether historical patterns of rebellion might indeed reemerge amid growing frustrations.

The intent and anticipatory actions of contemporary politicians appear to align more with constraining freedoms than with promoting them. If leaders truly aimed to restore faith in democracy, they would address the sources of citizen frustration rather than exacerbating issues through increased social and economic control, as evidenced by legislative initiatives that reinforce state authority. The passing of acts such as the Patriot Act and the National Defense Authorization Act signals a disturbing trend, emphasizing the need for increased control under the pretense of security. This parallels historical paradigms of governance where the state, under tyrannical rule, gradually stripped citizens of their rights, raising disquieting prospects of a modern feudalism under a different guise—a scenario where citizens relinquish their virtues of freedom for a semblance of security that ultimately renders them impotent.

Ultimately, the contemporary iteration of feudalism manifests not in the overtly oppressive tactics of previous eras but rather in the subtle manipulation of political structures that disenfranchise the populace thrust into economic dependency and apathy. Political factions that appear to operate independently on the surface often reveal a more troubling reality wherein they serve a shared interest, facilitating the maintenance of power structures that ultimately serve powerful financial and political elites over the common populace. This seamless integration of power and control orchestrated under the guise of democracy presents pressing questions about the future of governance in the First World. The historical parallels suggest a potential downward trajectory, urging a critical reflection on the importance of civic engagement and the necessity for citizens to reclaim their agency before this newly developing form of modern-day feudalism becomes irrevocably entrenched.