In the discussion regarding the complex relationship between macroeconomic indicators and household sentiment in the United States, Mike Shedlock highlights a notable paradox where objective economic metrics show positive trends, yet consumer sentiment remains low. As of September 2024, the unemployment rate was reported at 4.1%, significantly lower than the historical average of 5.7%. Moreover, the real GDP growth for the past four quarters reached 3.0%, wages have increased beyond inflation by 0.9%, and the stock market surged by 23%. Since the pandemic’s onset, there has been a massive increase in household wealth, with a staggering $50 trillion expansion, even as real median wages for lower-income workers have shown positive growth. Despite these favorable conditions and improvements in wealth and earnings relative to inflation, consumer sentiment appears dissonant and is nearing all-time lows, leading to a critical analysis of why this disconnect exists.

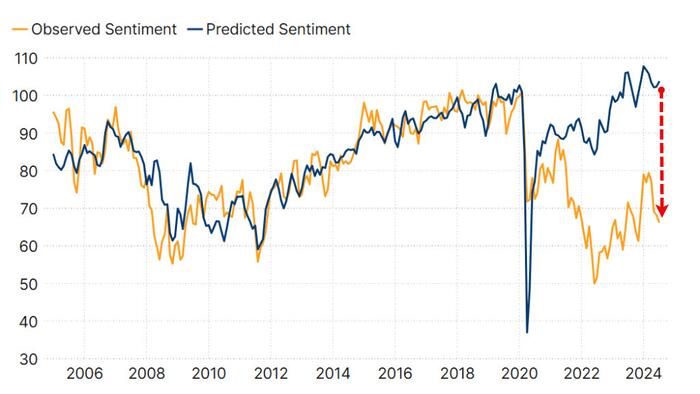

A deeper look into the informational landscape reveals a stark contrast between consumer sentiment and economic fundamentals. Historically, financial models utilized various macroeconomic variables, including unemployment and inflation rates, to successfully predict consumer sentiments. During the 2005-2019 period, a model could explain 77.4% of sentiment variations based on these parameters. However, since the pandemic’s impact, this relationship has unraveled, creating a substantive gap between actual observed sentiment and what economic conditions suggest should exist. Consumers presently exhibit discontent with the economy despite being situated within a relatively stable macroeconomic framework, indicating that perceptions of the economy may be driven by different influences.

Several theories have emerged to explain this phenomenon. Greg Ip from the Wall Street Journal proposes the concept of “referred pain,” where external factors such as political strife, social unrest, and global events may dampen economic perceptions. This stance suggests that even when objective economic conditions improve, psychological influences from a tumultuous political and social landscape could overshadow these positive metrics. However, some of the violence trends and international conflicts cited as contributing factors have shown signs of stability or improvement, creating a narrative challenge to this explanation.

Another perspective introduced by economist Jason Furman is that the pace of real wage growth in the post-pandemic period does not match the rapid gains seen prior, potentially leading to skepticism about sustainable economic improvements. Yet, this reasoning is complicated by the variability in what constitutes ‘real wage’ growth, highlighting the difficulties inherent in correlating wage data precisely. Furthermore, it’s puzzling that older households, which have faced declined employment rates, report similar sentiments to those of younger generations, without a clear linkage to wage changes, indicating a multifaceted sentiment framework.

On a more critical note, Shedlock addresses the disconnect from “ivory tower” reasoning, pointing out discrepancies in reported crime statistics and labor data that suggest a less rosy picture below the surface. Misreporting regarding violent crime rates by the FBI and a significant revision of 818,000 non-farm payroll jobs highlight an alarming trend that could foster a sentiment of insecurity despite economic metrics suggesting otherwise. The recent upturn in crime and growing difficulty among individuals to manage basic living expenses are stark realities that contradict theoretical optimism derived from macroeconomic data. As it stands, even high-income households struggle, with a significant portion living paycheck to paycheck, potentially stressing the unsustainable nature of current economic perceptions.

To pull these insights together, it’s striking to note that while the stock market is at an all-time high, reflecting significant corporate and investor confidence, the average American grapples with rising living costs, stagnant wages, and fears surrounding job security and housing affordability. Shedlock outlines that essential indicators, such as the rapid rise in housing prices and increasing eviction rates, contradict a bright economic outlook that some sentiments suggest. The housing market is characterized by soaring prices, with homes appreciating nearly 50% over a short span, complicating the lifecycle of home ownership for first-time buyers, resulting in widespread wealth disparity and financial strain. Considering all these variables, it’s evident that consumer sentiment is shaped not just by economic indicators but also by social and psychological dimensions reflecting a populace grappling with real economic challenges and expectations.

Ultimately, the paradox of a booming macroeconomy alongside precipitous declines in consumer sentiment underscores complexities in understanding public perception. While financial markets may paint an optimistic picture, the lived experiences of individuals define their realities. Shedlock’s exploration of this paradox emphasizes the need for a broader lens through which economic conditions are evaluated, using not only statistical measures but also integrating social and psychological insights into analyses of public sentiment. This multifaceted approach is paramount in unraveling why households feel anxious and pessimistic in a landscape riddled with politically charged narratives, social tensions, and the ongoing consequences of fluctuating economic indicators which don’t resonate meaningfully with everyday realities.