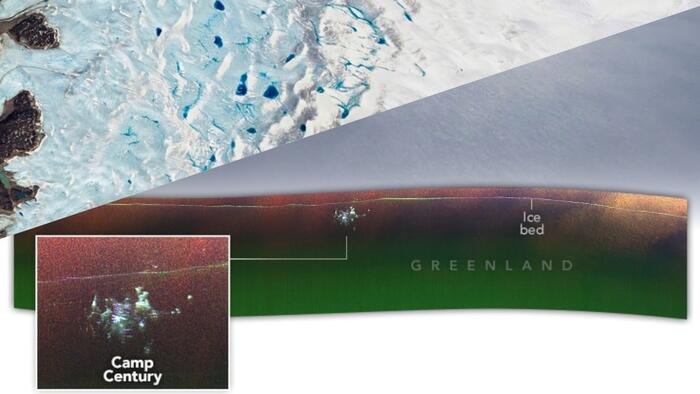

In the icy realms of Greenland, a striking discovery has emerged, revealing remnants of a hidden Cold War base known as Camp Century, which lies buried beneath a hundred feet of ice. Originally thought to be merely a radar scan of the frozen landscape, NASA’s advanced radar technology, specifically the Uninhabited Aerial Vehicle Synthetic Aperture Radar (UAVSAR), has unveiled intricate underground structures, providing a vivid glimpse into this area, previously cloaked in secrecy. Alex Gardner, a cryospheric scientist involved in the discovery, emphasized the unexpected nature of the find, as the team had initially aimed to explore the earth beneath the ice rather than uncover a relic of recent history. As scientists delve into this enigmatic “city under the ice,” they anticipate that it holds critical secrets about Cold War dynamics as well as contemporary environmental challenges caused by climate change.

Established in 1959 by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Camp Century was wrapped in a layer of deception, masquerading as a scientific research station while serving as a key component of Project Iceworm—an initiative aimed at determining the feasibility of launching nuclear missiles from beneath Greenland’s ice sheet against the Soviet Union. The facility provided basic necessities, including laboratories and living quarters to support scientific endeavors, which obscured its military ambitions. Nonetheless, it was the installation’s deeper purpose—to construct a network of tunnels intended to house and potentially launch the “Iceman” ballistic missiles—that made it a pivotal element of U.S. Cold War strategy. Ambitiously built, it faced serious structural instability due to the dynamic nature of ice, leading to its eventual decommissioning in 1967.

The engineering achievements realized at Camp Century were remarkable. Using a “cut-and-cover” method of construction, the camp comprised protective tunnels specifically designed to withstand the harsh conditions of the Greenland Ice Cap. A portable nuclear reactor, the PM-2A, powered the base, allowing it to function as a self-sustaining facility equipped with living quarters, kitchens, and even a movie theater. These engineering innovations not only served military purposes but also contributed to advancing cold region engineering techniques, shaping how future operations might be conducted in extreme environments. The experiences and data harvested from its operational phase offered invaluable insights that could be applied to subsequent designs for similar facilities, confirming that subsurface ice-cap camps can indeed be practical.

Despite its initial façade of scientific exploration, the true nature of Camp Century was revealed in 1997 following the publication of classified documents by the Danish Parliament. The shocking disclosure indicated that Camp Century had secretly been intended as a nuclear missile launch site, undermining trusted U.S.-Danish relations and initiating discussions about the ethical dimensions of such military operations in Greenland. The notion of a research station pivoting towards military objectives highlighted potential conformity violations within national sovereignty and displayed a breach of trust with Denmark. As global awareness grew surrounding these revelations, it raised significant questions about the environmental responsibilities relating to the hazardous materials buried beneath the ice.

As global temperatures continue to rise, concerns are mounting over the potential environmental repercussions of Camp Century’s collapse beneath melting ice. Projections indicate that by 2090, the camp and its buried materials, including 9,200 tons of physical debris and an alarming 53,000 gallons of diesel fuel, may become exposed. Among the most pressing issues is the fate of the radioactive waste and persistent pollutants like polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), which could seep into ecosystems, bioaccumulating and posing severe risks to wildlife and human health. The potential for these contaminants to resurface as the glacier melts underscores the environmental dangers associated with the remnants of Cold War militarization.

The rediscovery of Camp Century serves as a compelling reminder of the intricate relationship between human activities, geopolitical maneuvering, and environmental consequences. As potential threats from the past begin to emerge, tackling the associated cleanup and management of hazardous materials will require coordinated international efforts, drawing in multiple stakeholders, including the U.S., Denmark, and Greenland. This situation encapsulates not only the environmental impacts of climate change but also the ensuing political conflicts borne out of historical military operations, compelling us to seek responsible stewardship and accountability across generations. As the ice holds echoes of military ingenuity frozen in time, the challenges posed by Camp Century remain a stark lesson about the repercussions of prioritizing geopolitical ambitions over environmental integrity.