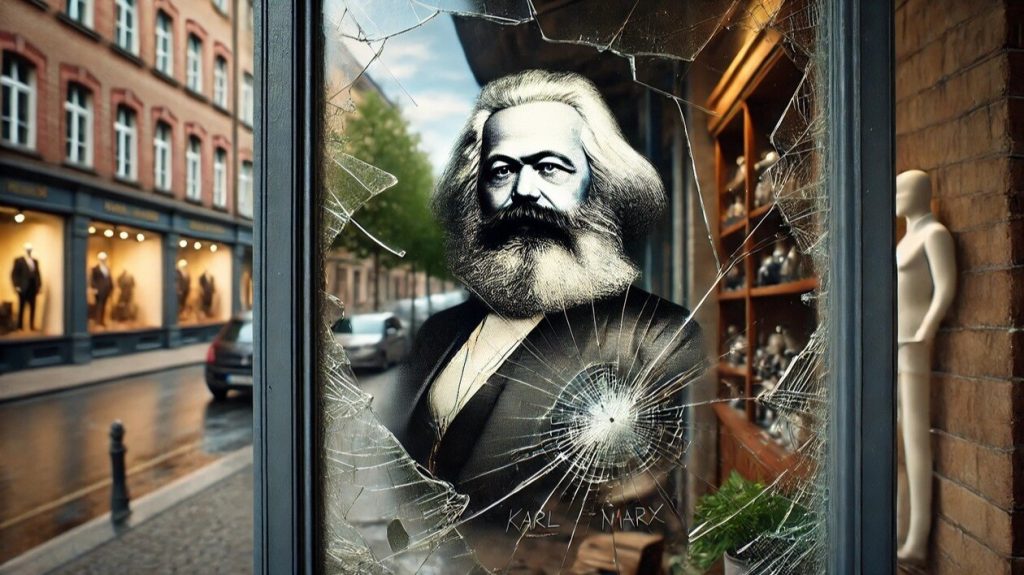

In contemporary discourse surrounding economic distress, issues such as heightened national debt, inflation, and market fluctuations are often attributed to the concept of “late-stage capitalism.” However, as Joshua D. Glawson argues, should these economic struggles rather be characterized as symptoms of “late-stage Keynesianism”? This perspective posits that the failures observed are not inherently linked to free-market capitalism but stem from a variant of economic policy reliant on government intervention, fiat currency, and the misguided belief that artificial governmental spending can lead to sustainable prosperity. Through a reevaluation of Karl Marx’s stages of capitalism, Glawson invites readers to consider these economic challenges not as a reflection of market failures but as the outcomes of Keynesian economic theories.

Marx outlined several phases of capitalism characterized by increasing exploitation and inequality leading to eventual collapse. These stages included primitive accumulation, manufacturing capitalism, industrial capitalism, financial capitalism, and finally, late-stage capitalism. Glawson asserts that many dynamics identified by Marx—a movement toward centralization, inequality, and reliance on speculative financial markets—are not necessarily inherent to capitalism itself but rather manifestations induced by Keynesian economic policies and government interventions. By associating these stages with Keynesianism, Glawson suggests that the current economic predicament is misidentified as a failing of capitalism when it is, in actuality, a product of misguided interventions by the state.

The first stage, primitive accumulation, describes the gathering of wealth without efficient markets. In today’s context, Glawson likens this to the use of fiat currency and arbitrary credit expansion, which allow governments to create money without tangible backing. Such actions result in wealth concentration among the elite, as inflation erodes the purchasing power of the general populace, a scenario impossible under a gold-backed currency system. Subsequent to this, the manufacturing phase is equally marred by intervention; subsidies and labor legislation favor large corporations, which can weather regulatory burdens far better than smaller competitors. This regulatory environment leads to an unnatural centralization of control over labor and production, distorting the idea of a competitive and free market.

In examining industrial capitalism, Glawson emphasizes how Keynesian policies further contribute to economic instability through debt-driven growth and state-led investments. Fiat monetary expansion allows corporations to thrive beyond their sustainable means, resulting in economic bubbles that subsequently lead to financial corrections. Additionally, state involvement in infrastructure prioritizes government-selected investments over market-driven choices, thus skewing the allocation of resources and enhancing inefficient economic practices. Financial capitalism, characterized by speculative practices rather than production, gains momentum from central banks’ manipulation of interest rates and practices like quantitative easing. These dynamics, fueled by Keynesian regulations, foster wealth inequality, as financial gains primarily benefit asset holders, detracting from genuine wealth-creating activities.

Glawson also differentiates between coercive and voluntary monopolies within economic discourse. While commonly criticized as a downside of capitalism, voluntary monopolies stem from genuine market success where companies offer unique or superior goods or services. In contrast, coercive monopolies arise from government protection and regulatory advantages, relying on special privileges like subsidies and bailouts. The prevalence of coercive monopolies in modern economics serves to illustrate the flaws in a system that continuously favors established interests through government interventions, deviating from the principles of free market competition that would naturally regulate monopolistic tendencies.

The chemise of late-stage Keynesianism is fundamentally intertwined with unsustainable debt and economic manipulation via fiat currency, which cumulatively foster crisis-prone economies. Persistent government borrowing leads to a reduction in productive investment and reliance on constant economic stimulation to maintain growth illusions, creating fragile economic structures prone to fluctuation and downturn. The underlying issues often yield heightened inflation and significant currency devaluation, undermining wage earners’ purchasing power while benefiting broader financial markets. Hence, though they echo Marx’s warnings regarding late-stage capitalism, these phenomena result from Keynesian strategies rather than intrinsic flaws in capitalist structures.

Ultimately, Glawson questions the narrative framing contemporary economic challenges as failures of capitalism, positing that these issues may stem from extensive Keynesian interventionism. A truly functioning capitalist environment, characterized by sound money and limited government involvement, would foster genuine economic growth propelled by savings, productive investments, and market-driven success. The call to action emphasizes the necessity for a reassessment of economic theories—advocating for a return to free-market principles to nurture sustainable economic growth devoid of artificial distortions introduced by interventionist policies. The present economic turmoil may, therefore, warrant a diagnosis of late-stage Keynesianism and not late-stage capitalism, revealing an urgent need to reembrace foundational market principles to achieve a stable economic framework.