In the discourse surrounding central planning and its implications on economies, Charles Hugh Smith’s analysis sheds light on the recurring illusion of sustained success that typically accompanies initial central planning initiatives. This is notably seen in China, which serves as a poignant real-time case study. Here, central planning shapes the economic landscape through strategic decisions made by the state regarding goals, financing, and regulation, fundamentally redirecting the economy’s course. For instance, historical parallels in the United States, like the wartime shifts during World War II and urban redevelopment through highway construction in the 1960s, underline the multifaceted impacts of government-led initiatives. The focus now shifts to China, where an economic miracle transitioned from historic dilapidation in living conditions to a rapid urban industrialization driven by central planning.

The transformation of China’s housing market emerged in the 1990s when the government introduced land leasing, transitioning ownership from the state to individual households while retaining property rights. This model was designed not to create a vibrant market for housing but to alleviate the state’s financial burden by transferring housing costs to the private sector. Urbanization necessitated this transition as millions migrated from the countryside to cities. Local governments could sell land to real estate developers, offsetting government expenditures while simultaneously stimulating job creation in the construction sector. This structure seemingly established a land of plenty: housing construction surged, locals found employment, and increasing personal savings could be leveraged to secure homes, ostensibly leading to a stable real estate market.

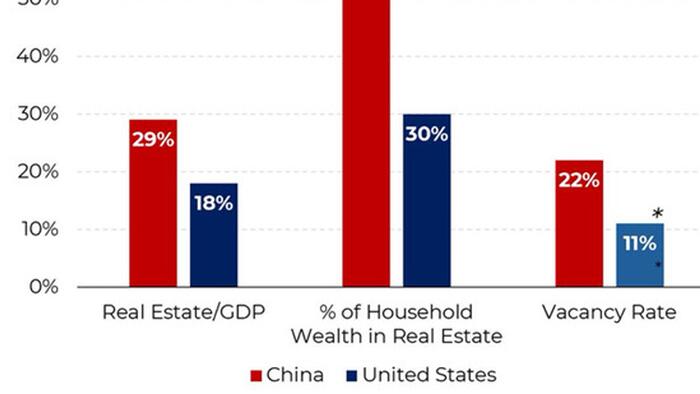

However, an underlying flaw framed this booming micro-economy — the absence of a functional resale market for homes. Unlike traditional real estate markets where homes gain value through competition and genuine demand, China’s existing housing units became indirectly tied to the increasingly high prices of newly constructed properties. This artificial inflation led to a false sense of wealth among homeowners, predicated on the assumption that housing values would continue to rise indefinitely. Nonetheless, as the central planning model progressed and new developments continued, the real market value remained obscured, creating a façade of prosperity that ultimately disintegrated, revealing a stagnant and impoverished housing market exacerbated by oversupply and diminished consumer confidence.

As a consequence of the central planning model, China finds itself in a precarious situation marked by an enormous surplus of housing, illustrated by staggering estimates of over 94 million empty homes and around 120 million incomplete or unstarted projects. These figures point to a systemic distortion propagated from a planning process stripped of adequate market feedback mechanisms. With developers habitually leveraging buyer pre-sales to fund new land acquisitions, many of these developers find themselves cash-strapped, unable to deliver on their commitments, and leaving countless homebuyers in dire situations with half-finished investments. Expanding the ramifications of this situation reveals a bitter truth: these households often bear the brunt of financial burdens linked to non-existent or incomplete living accommodations.

The entrenchment of influential interests within the centralized planning mechanism leads to a distortion of accountability and oversight within the housing market. Banks, developers, and even local governance entities each arise as fulcrums of financial incentives, creating a wall that impedes necessary reforms or adjustments against an unsustainable business model. This phenomenon fosters an ecosystem where entrenched interests solidify their influence, perpetuating a cycle of misallocation of capital and intensifying the housing crisis. The absence of mechanisms to effectively address burgeoning risks and losses furthers the accumulation of systemic debt, the repercussions of which become the burden of ordinary citizens, amplifying the social malaise pervasive across affected regions.

Evaluating the lessons from China’s central planning architecture reveals several crucial insights. Successful central planning can initially unleash dormant productive capacities and stimulate growth, establishing winners in the process. However, as these winners consolidate power, they inevitably become resistant to necessary oversight, contributing to entrenched systemic risks. Furthermore, the unfettered focus on private capital without structural safeguards leads homeowners to face potentially grave financial outcomes; in various instances, citizens navigate the fallout of purchasing half-finished properties while contending with mounting debts. These realities illustrate the inherent weaknesses of centralized economic models, encapsulating the friction produced when aspirations of perpetual success conflict with the harsh realities of unsustainable planning practices.

Ultimately, as far-reaching distortions arise from central planning endeavors, the systemic failures become increasingly apparent. The model initially heralds success, yet yields a self-liquidating cycle whereby economic growth transitions to debilitating stagnation marked by the accumulation of inevitable losses. The lessons learned extend beyond China and speak to the vulnerabilities inherent in central planning, highlighting a necessity for economic frameworks that embrace transparency, adaptability, and genuine market feedback as safeguards against the inevitable pitfalls of entrenched interests. The absence of these elements not only endangers the stability of specific sectors but threatens the equilibrium of the wider economy, forcing stakeholders to confront the reality that the ongoing success of central planning is, at best, a temporary illusion.