In his recent blog post, Charles Hugh Smith examines the clear signs of a global recession, highlighting a comprehensive list of 17 key indicators compiled by correspondent Wilson R. Logan. According to Smith, these indicators serve as alarm bells, signifying that a recession is not only imminent but already underway. He emphasizes the interconnectedness of the global economy, where disruptions in one sector can ripple through and amplify challenges across systems, leading to a cascading effect reminiscent of an avalanche. This observation sets the stage for a deeper look at the various factors that signal an impending downturn, suggesting that the warning signs have been evident for some time.

Logan’s list includes critical indicators such as tighter credit conditions, increasing REPO fails, and various forms of yield curve inversion, reflecting increasing economic uncertainty and decreased confidence among financial institutions. The falling oil prices and negative sentiment in consumer surveys add further context to the overall bleak economic outlook. Smith underscores the significance of each indicator, arguing that they are symptomatic of a larger systemic issue. In particular, he notes that rising credit card debt and decreasing factory gate prices reflect a waning consumer capacity to spend, signaling that both households and businesses face growing financial strains.

Smith also introduces the concept of an “inverted pyramid of debt and disposable earnings,” which illustrates the precarious balance between debt servicing costs and disposable income. This framework applies universally—from individuals and households to corporations and nation-states. He emphasizes that as inflation diminishes purchasing power, individuals are compelled to rely on debt to maintain their spending habits. However, he warns that rising interest rates can quickly turn this situation unsustainable. This discussion of “Zombie Corporations” brings home the point that many businesses survive by rolling over their debt under favorable conditions, but become vulnerable when access to credit tightens.

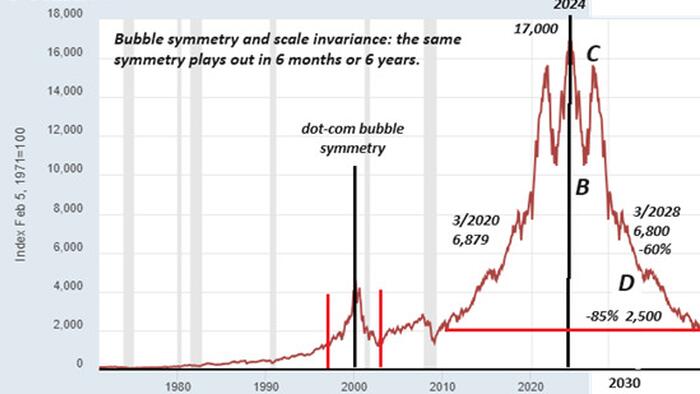

Bubbles within financial markets are another fundamental theme of Smith’s analysis. He argues that when a financial bubble is considered “impossible” to burst, it is often a clear signal that trouble lies ahead. He identifies the current global “Everything Bubble” as an archetype, suggesting that its eventual deflation is inevitable. The cyclical nature of bubbles—characterized by symmetrical ascents and descents—leads Smith to project that the collapse of the Everything Bubble will occur with similar certainty. His argument is intensified by the notion that reliance on speculative ideas of perpetual growth can lead to misguided confidence in the financial markets.

The consequences of these indicators and systemic vulnerabilities are dire, with Smith asserting that creditors may face significant losses as the cycle of insolvency unfolds. He points out that while bankruptcy may absolve some debtors, it can devastate lenders and investors who lose substantial assets in the process. In discussing the potential for widespread financial collapse, he notes that economic mitigation strategies can be rendered ineffective in the face of tightening credit conditions and rising interest rates.

By the conclusion of his analysis, Smith stresses that the smart money is already reacting—selling assets and preparing for the consequences. The repetitive alarms of recession highlight that the banquet of consequences has been served, and inaction during this pivotal period may prove disastrous. He invites readers to contemplate these indicators seriously, framing his perspective as a warning to those who remain overly optimistic about the future of the economy. The message is clear: the time for complacency has passed, and vigilance is now necessary to navigate the turbulent waters ahead.