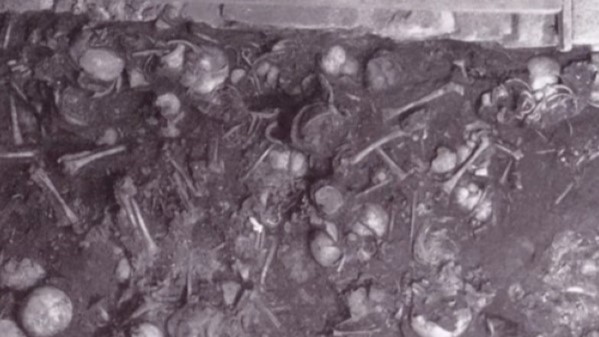

Recent research presented at the “Water and Life” meeting in Mexico has shed light on a significant archaeological discovery from the 15th century. Excavations at the Templo Mayor, the major temple complex of Tenochtitlán, led to the unearthing of the skeletal remains of at least 42 children, aged between 2 and 7 years. Initially found during excavations in 1980 and 1981, these remains were discovered laid out in a manner that suggests ritual significance, with their bodies positioned within ashlar boxes on sand layers. Some of the remains were adorned with ornaments such as necklaces and had green stone beads placed in their mouths, indicating that these children were likely sacrificed in a ritual to appease the rain god, Tláloc, during a devastating drought.

According to research led by archaeologist Leonardo López Luján, the mass sacrifice of children corresponded with a severe drought across central Mexico between 1452 and 1454. The drought, which lasted for several years during Moctezuma I’s reign, resulted in catastrophic food shortages and compelled many desperate families to resort to selling their children for sustenance. This period was marked by immense suffering and hardship, compelling the Mexica state to take urgent action to alleviate the crisis. Initial efforts included redistributing food supplies from royal granaries to the most affected populations, combined with the ritual offerings intended to placate Tláloc and his assistants, the tlaloque, who were believed to have control over rainfall.

The INAH researchers utilized geological data in conjunction with entries in the Mexican Drought Atlas to establish a timeline and context for the drought, elucidating its devastating effects on the agricultural landscape. The combination of summer droughts and late autumn frosts undermined the agricultural cycle, obstructing the growth of maize and leading to widespread famine. López Luján indicated that this multi-faceted agricultural failure created a dire situation, pushing the Mexica society to the brink of collapse and ultimately contributing to the exodus of people from affected areas.

The children who were sacrificed were treated with ritual significance; their bodies were decorated with blue pigments, small bird remains, and seashells. Furthermore, the surrounding area featured 11 sculptures composed of volcanic rock designed to resemble the visage of Tláloc. The elaborate adornment of the children suggests an intentional connection to the rain deities, as it was common in Aztec culture to invoke divine favor through such offerings. It is implied that by decorating the children to resemble the tlaloque, the Mexica aimed to influence the supernatural forces that governed their agriculturally dependent society.

Notably, this aspect of Aztec spirituality underscores the depth of cultural practices in response to natural disasters. Rituals like the mass sacrifice highlight not only the desperation amid the drought but also the societal structure that influenced such events. Children, often seen as pure and connected to the divine, were selected for these rituals, reflecting the severe measures that were taken in times of crisis. The interplay between faith, desperation, and governance in the face of environmental calamity points to a complex worldview that held nature’s favor in high regard.

The findings from Templo Mayor signal an important reminder of the intertwining of human experiences with environmental changes throughout history. As droughts and famine drove societal decisions, the archeological evidence invites us to reflect upon the broader implications of climate on civilization. The ritualistic practices derived from such severe circumstances demonstrate humankind’s enduring quest to seek understanding and control over the forces of nature, revealing both the fragility and resilience of cultures in their attempts to weather existential threats. The revelations coming from these significant archaeological finds continue to illuminate the historical narratives surrounding the ancient Mexica civilization and their responses to crises of monumental proportions.